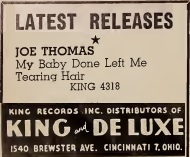

Joe Thomas: “My Baby Done Left Me”

08 Friday Feb 2019

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

KING 4318; OCTOBER 1949

Most of the artists from this era were never asked to recount their careers and by this point in time there are so few of them left that we’ll probably never really know what any of them were thinking when it came to the musical choices that they made back then. Was a move from one style to another a conscious decision or was it forced upon them by record labels? In some cases did the artists in question even know they were making a move from one type of music to another, or was it merely just a slight variation not worth thinking much about?

Joe Thomas lived until 1986 and so he was certainly around long enough to ask, but apparently nobody ever did. He’d gotten out of music years before and become a mortician so maybe interviewers were hesitant to go nosing around for fear he might think they were in the market for a coffin or something.

But if there was ever an early rock act who you’d WANT to ask a few things of it’d surely be the guy who had been one of the most respected sax players of the swing era and who wound up slumming in rock ‘n’ roll just a few years later.

Back And Forth

Thomas was forty years old in 1949, hardly the time to start thinking of retirement, but the career he’d known was in its twilight. Shorn of the security of a nationally famous band with a huge following in a style that had dominated the musical landscape for 15 years he was left to flounder about looking for a reasonable alternative.

He’d hired George Duvivier, a bassist and arranger with whom he formed a smaller band after his efforts at keeping Jimmie Lunceford’s larger swing outfit intact had fizzled and so you could certainly say he was inching towards this eventuality already, but that process was sped up because of the events swirling around him that he had nothing to do with.

Thomas was being booked by Universal Attractions, one of the leading talent agencies in the country who were responsible for matching their clients with venues where they both could make money. In 1949 however the venues that he’d been used to with Lunceford were drying up, or at least the audiences for those venues were drying up. But another style was getting bigger by the minute.

Though again we have to point out that apparently nobody bothered to ask Thomas about this, thankfully somebody DID sit down with Duvivier who explained, “The late 1940’s was a peculiar transition period in music… so called rhythm and blues, which was the foundation of what was later called rock and roll, was taking hold. Universal wanted his group to be an R&B oriented band. Joe didn’t want to do it because he wasn’t a rock musician and hadn’t made his reputation playing that sort of music…”

Can you see where this headed?

When King Records signed him up in mid-1949 they weren’t interested in the bigger band arrangements Thomas was used to either. They wanted rock ‘n’ roll.

They got their way more or less with a four song session Thomas cut May 21st, of which this single was the second release (after Backstage At The Apollo which came out last spring), but the results of all of these sides were a little ambiguous. They were rockish, rock-like maybe, (or rock-lite if you prefer), but hardly a compelling reason for rock audiences to embrace them wholeheartedly… and without that fervent response from the desired constituency it was unlikely that Thomas would throw in with the music without reservation. So King – maybe intentionally, maybe just fortuitously – wound up crediting Thomas as the lead artist on a Todd Rhodes rock instrumental which Thomas DID play on, but not as the leader.

When that song, Page Boy Shuffle, became a huge hit, Thomas’s choice was made for him.

So then what do we make of his efforts cut BEFORE that song got wrongly attributed to him and he was still merely trying this sound on for size, unconvinced of its merits perhaps but willing to give it a shot all the same. How lenient are we in our assessments when the results of those tentative experiments were songs like My Baby Done Left Me, something intentionally crude but surrounded by some classier attributes.

I Tried So Hard To Be Good

Everything about this record speaks to the inherent conflict with their aims. They were expected to rock and so they added definite rock elements to an arrangement that was classier than it should be if they were genuine in their attempts at fitting in.

This is evident five seconds into My Baby Done Left Me… before the vocals even come into the picture and let on what was about unfold, as the first sound we hear is Thomas’s sax blowing strong with a drum kick behind him that places this squarely in the rock territory that King Records was hoping they’d align themselves with.

Then the other horns show up and pull the rug out from beneath them and the reason is hardly surprising… there’s just too damn many of them.

Two trumpets, a trombone and a baritone sax! That’s a total of five horns on this record, including Thomas himself of course, which means you could make a basketball team out of the brass and reed section. I’m not sure if any of them had a lick of athletic talent but I’d rather see them try and sink a free throw or run a pick and roll than intrude on the gutsier sound that Thomas by himself was creating before they jumped off the bench and ran to the scorer’s table to check in.

Their arrival throws the entire balance of the song into disarray and it’s only just started. The initial vibe Thomas gave off was rough-hewn while their contributions are anything but. But even Thomas is hampered by the fact he’s being asked to do two things, play and sing, only one of which is really of high quality and unfortunately to do the other he has to stop doing the one he’s good at. As soon as he drops his sax to start singing – and I use that term very loosely – the record derails even though he’s trying so hard to be convincing that you’re afraid he might bust a blood vessel in the attempt.

The lyrics he sings are pretty standard fare, which is another way to say they’ll suffice if everything around it provides good support. In this story we have yet another guy who lost his girlfriend – this is becoming an epidemic in rock lately, maybe we should start a support group – and because of the frequency of this theme by this point we don’t really even need to get into the particulars of WHY. It doesn’t matter. The point is she’s gone, he’s sad, cue the distraught histrionics as he claims he can’t figure out why she’d leave a great catch such as him.

All well and good. We won’t find fault in the details, that is if we’re even paying attention, because we have a far more pressing problem on our hands, namely the fact he’s of the mistaken belief that rock singing isn’t concerned with singing so much as it is with making an indescribable noise. I believe the technical term for what he’s attempting to do is caterwauling.

The more he tries to wring anguish out of his vocal chords, the more alarmed we become. We’re not concerned for his well-being so much, but rather we’re concerned for ours. He garbles some words, twists others, screams and hollers and does everything short tying his tongue around the railing of a bridge before leaping off to show how much pain he’s in but none of that is necessary. We know he’s in pain because so are we just listening to him.

I’m Gonna Get ‘Im On The Track

I suppose it could be worse, he could try and croon it, or softly sob as he choked the words out, in which case the accompanying music would sound rousing by comparison. But because he’s so animated himself the band merely sounds inappropriate by comparison no matter how spry they may be. That’s hardly surprising after all, since there’s only so much you can do when the horns in question are a holdover from another idiom.

How do we critique thee? Let us count the ways:

Their sound is too shrill, their arrangement too orderly, their energy too artificial. They’re lacking a bottom… lacking a balance… lacking balls really – and no, I’m not referring to basketballs anymore. You need to dump them all, save for the baritone sax, and with him you need to put some burrs in his saddle or stones in his shoes and have him respond to that discomfort in his retorts to get the proper bellows from his horns. As it is he remains a woefully underused weapon. If you want the basketball analogy again, he’s like a good post player never getting ball thrown down low to take advantage of him.

When Thomas stops screaming and starts blowing things drastically improve however. His solo on the tenor is alternately mesmerizing and seductive and crude and unruly. He even gets a low honk in that the baritone refused to give us. This isn’t long enough to suit us by any means – though truthfully an instrumental featuring him playing what he does in his brief spots here on My Baby Done Left Me would be far better for everybody involved – but don’t let it be said that Joe Thomas didn’t have what it took to hold his own in the rock sax battles of this era.

The rest of the band actually acquit themselves fairly well even without much of a chance to shine. The drummer gets some good thwacks in, the bassist provides a steady throbbing pulse to let you know that the rhythm section hasn’t expired, and even pianist George Rhodes chips in with a few licks that fit in with the program. But it’s not enough, not when Thomas has to keep his weapon holstered for far too long just to be able to deliver the story.

Walked Right Out The Door

Though we have little choice but to be pretty harsh on the elements that don’t work on this record, it’s just as hard, if not harder, to try and see past those deficiencies to commend its attempt at conforming to the requirements of a brand of music they surely wouldn’t have chosen without some prodding by those paying the bills.

They were formed out of the remnants of a big swing band and so it was going to have an out-sized horn section. But those guys COULD play after all, they just couldn’t play this music with the natural unforced feel it requires. But once Thomas has to relinquish the lead instrument there’s little choice but to let the others in the brass section take that role over and they aren’t going to deliver what we need in this realm to satisfy us.

As for letting Joe sing in the first place? He could do that too, as he’d shown to far better effect on some Lunceford sides, and even at times here, when he actually sings and not screeches that is, he shows he’s got a decent voice. Besides we’re always preaching how bands need to diversify their output and since the flip side to this, Tearing Hair, was an instrumental it was sensible to pair it with a vocal, it’s just that they badly misjudged the vocal technique necessary to connect with rock fans.

In the end that’s the real shortcoming – their lack of familiarity and comfort with rock. They hadn’t grown up with this music, hadn’t been shaped by it, hadn’t even seen the response they could get by playing it well, yet they (admirably, I suppose) tried to play it all the same. Parts of My Baby Done Left Me managed to pull it off fairly well, but those parts were book-ended by parts that should’ve been amputated altogether.

So what you get is a mismatched Frankenstein’s monster. A head from one body, arms from another trying to stand on legs from someone else. It’s no wonder this girl left, she probably just couldn’t find him any clothes to fit such a mismatched body and wanted to hit the town anyway so she dumped him.

Given the circumstances, who can really blame her?

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of Joe Thomas for the complete archive of his records reviewed to date)