Roscoe Gordon: “Love You ‘Til The Day I Die”

29 Monday Aug 2022

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

Share it

CHESS 1487; NOVEMBER 1951

Perfection is not a constant in life, it’s an anomoly.

That’s hard for some of us to accept. When we manage to do something that comes off without a flaw the ensuing feeling of pride, the sense of accomplishment and the boost to your ego are all so powerful that you not only crave that sensation again, you come to think of it as your birthright.

But sometimes the stars just have to align properly to reach that plateau and each time out you have to re-align those stars for it to happen again.

On the top side of this release Rosco Gordon had all those stars lined up perfectly – the right song, the right arrangement, the right delivery. Yet on this side, cut at the same session, the stars were obviously scattered in the skies behind heavy cloud cover.

Can’t Make You Do Right

This is the first chance we’ll get to encounter an artist whose future presence on these pages might be sporadic but whose importance in music history over the next quarter century will be immense.

Bobby “Blue” Bland is most often referred to as a blues singer… in fact he himself might attest that was his main occupation… but he did more than just dabble in rock ‘n’ roll on the side, many of his biggest hits and most enduring songs were rock in their construction, delivery and audience reception.

But in 1951 Bland was still a musical nobody, another aspiring artist out of Memphis who happened to find himself singing with a loose-knit group of future stars dubbed The Beale Streeters which included B.B. King as he was about to make his ascent to stardom, but also drummer Earl Forest, pianist Johnny Ace, saxophonist Adolph “Billy” Duncan and another pianist Rosco Gordon… all of whom also sang with the exception of Duncan.

With so many guys in the group who could handle vocals as well as pick up the musical slack better than Bland, who plays guitar here but was hardly more than adequate on the instrument and never would play on his own records, he clearly had fewer options when it came to getting noticed and so he turned to writing to boost his chances at earning a bigger shot at the brass ring.

Love You ‘Til The Day I Die earned him that initial shot but he wound up setting himself back in the process, for neither the song itself nor Bland’s uncredited vocal contributions to the record were going to help his long term prospects in any way, shape or form.

In fact, the song was so muddled that it’s surprising that Bland managed to get even one more chance to show what he was capable of doing, because record labels, not to mention audiences who valued good songs, were unlikely to want to hear anything coming from his pen or his mouth again after suffering through this mess.

You Said You Wanted Me Just By Yourself

The theme and the title have obvious appeal. A definitive statement of intent when it comes to love may backfire in real life, but in the context of a song without any personal implications for the listener it tends to be received a bit more generously as an unwavering sign of devotion.

Unfortunately we get two voices, not one, delivering this vow, one of which belongs to Bland, an artist who’d be known for having an indelible delivery, though it’s one he must’ve acquired months from now at a thrift store in Arkansas because it’s definitely not on display here.

He’s out of tune, out of meter and out of his mind by the sounds of it with the way he’s moaning. Gordon picks up the slack the best he can – at least when he’s contributing the primary lead rather than finding them singing different lines on top of one another which is downright cacophonous – but even then it’s not enough to redeem things by any means, only make them a little less off-putting for brief stretches.

They aren’t helped by the fact that Love You ‘Til The Day I Die has nothing much to offer in the story beyond the sentiment found in the title itself. The simplicity of the song might’ve worked better with a more subdued vocal delivery, but by trying to convey the despair they have when their woman (was this a polygamous relationship?) leaves them, they’ve eliminated any chance for nuance or subtlety. There’s so much emotional wailing going on in their vocals that it merely draws attention to how unfocused the narrative is and how they’re trying to substitute pure feeling for rational thought.

Musically it fares no better as the melody is left in tatters by the choppy inconsistent rhythm while the instrumental accompaniment, including Gordon’s lurching piano, is grating on the senses because it has so few notes to play. Even Billy Duncan’s sax which might have the ability to take some of the pressure of the rest of them, is doing little more than droning.

Gordon may have thought he was doing Bland a favor here, essentially giving Bobby his first break in the studio – something which Sam Phillips, by virtue of not specifying this was in fact another artist who perhaps should be get the lead designation, further hampered – but maybe it was for the best that Bland’s name not be dragged through the mud on this so he could escape much of the blame outside the writing credit.

It was his clearly own shortcomings which were at fault, but since he’d prove down the road to be a much greater talent than this unmitigated disaster suggested was remotely possible, maybe the nicest thing we can say about this record is we’re glad that whatever malady he had that impacted his performance here wasn’t fatal.

There’s No Use In Us Carryin’ On

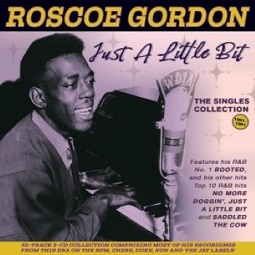

As monumental as Rosco Gordon’s career would be with a number of big hits stretching into the early 1960’s, not to mention his immense influence on Jamaican ska, his star was eclipsed by Bobby “Blue” Bland in the long run.

By the early 1960’s Bland was the primary artistic link between blues and soul with his horn driven (rather than guitar fueled) records which meant many of them, especially the rousing uptempo tracks, were perfectly at home in rock ‘n’ roll giving him rare cross-genre appeal at a time when blues was becoming much more of a niche field than it had been a decade earlier.

Because of that subsequent success Love You ‘Til The Day I Die remains far less obscure than he’d probably like, though clearly it didn’t do any of them – Gordon, Bland or Phillips – any serious harm.

The harm in the case is the listener’s eardrums as they’re forced to sit through a performance that would have to substantially improve just to be called caterwauling.

It’s an historical curio for sure, but a blight on their résumés all the same.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of Rosco Gordon for the complete archive of his records reviewed to date)