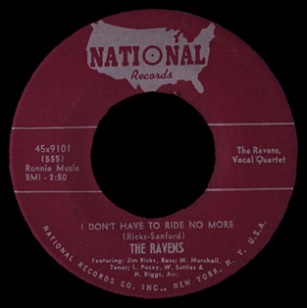

The Ravens: “I Don’t Have To Ride No More”

04 Tuesday Feb 2020

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

NATIONAL 9101; JANUARY, 1950

Though they were one of the top rock acts of the genre’s first half dozen years The Ravens – or maybe more accurately their record label, National – routinely made the same mistakes time and again, a process which basically consisted of three steps.

The first was The Ravens would cut pure rock-based material featuring bass vocalist Jimmy Ricks who was allowed full reign of his most compelling attributes, an earthy and slightly lecherous tone, something which not only gave the audience what they craved but which also set them apart from any other act in music since nobody had a voice with as much gravitas as Ricky.

The second step they’d take however would invariably send them in the opposite direction – a more pop-oriented style featuring the high tenor voice of Maithe Marshall, a good singer but one who most often used a thoroughly outdated delivery that refuted the carnal qualities of the group that Ricks had already laid bare.

When the commercial returns came in it was always the rock sides that the listeners sought out causing National Records’ high hopes for crossover appeal to the overlooked septuagenarian market to fall by the wayside prompting The Ravens to re-assess what they did best and cut some more rockers.

Then – instead of learning their lesson once and for all – they’d repeat steps 2 and 3 all over again until it made your head spin.

Why Should You Roam?

To be fair, when we criticize The Ravens for falling into the same quicksand we’re not talking about merely the difference between ballads and uptempo performances, even though it’s the more rhythmic stuff that we’ve given the higher marks to and which the listeners at the time chose with their wallets.

Giving audiences two different attributes on each side was in fact a sound theory, even if one was far more successful on a regular basis. You don’t want to wear out your best ideas by using the same tricks on each side, as The Ravens closest competitors – The Orioles – were always at risk for with their over-reliance on brokenhearted ballads on both the A and B-sides of their records.

No, what we’re talking about is HOW The Ravens approached those slower numbers as if it were 1942 and not 1950.

By sticking with pop-based mannerisms – open throated singing, over-enunciated vowels, light airy harmonies, tinkling piano, demure lyrics – they ran the risk of driving their biggest constituents away. Rock fans weren’t interested in that, if they had been then The Ink Spots would still be as big at the turn of the decade as they were at the turn of LAST decade!

As if to show how far astray they could get at times they’d taken The Shadows’ very good rock ballad from a month earlier and ruined it by accentuating the pop aspects of their version of I’ve Been A Fool on the top side of this single, rendering it all but impotent in the process.

But thankfully we don’t have to worry about that here, for I Don’t Have To Ride No More is unquestionably a rock song, supercharged and proud of it, and delivered in a way that only they were capable of doing justice to.

Everything You Want Is Here At Home

When reviewing the other side we realized within the first 15 seconds that we were already let down by the performance, knowing right away it was going to be a bad record, but here it doesn’t even take that long to know this is going to be a great one.

Kicking off with a pounding piano and skittering drums before The Ravens jump in with tight fast harmonies telling us to pack our bags to hit the road with them, we’re on board from the very start. Wherever they’re going, we’ll follow and if they keep singing this way I’ll even pay for the gas.

Jimmy Ricks’s bass voice is prominent in the harmonies, something which is always nice to hear, but it’s even better is when he steps out front to lead the song which is where everything falls perfectly into place. On I Don’t Have To Ride No More he’s back in the saddle, revved up and raring to go – horny by the sounds of it, but the lyrics are kind of vague so we’ll leave the particulars aside for the moment and just focus on the sheer honeyed tones oozing from the speakers as he gets into gear.

This is what Ricky does so well, burning rubber off the line before downshifting into cruising speed, knowing just when to ease off coming into a turn and when to step on the gas coming out of it. It’s never been just his peerless voice that makes him arguably the best pure singer of his generation in rock, but the fact that he wields it with such unerring control. Fast or slow, happy or sad, he’s always the one you want behind the wheel. On this track in particular there’s such infectious joy in his voice that you can’t help but be caught up in it.

It’s not surprising to find that Ricks himself wrote this – maybe he was dreading another meandering stroll through the great American songbook – because all of the traits he specialized in are featured here, from the aforementioned pace changes to the stop-time bridge where he gets to relish driving each point home, to the Greek chorus chanting of the others behind him at times – Ri-ide! Riiii-ide! Ri-ide! – and the stabbing piano that emphasizes the urgency of it all.

In that way it’s almost like a roll call of their greatest hits, and in fact it definitely conjures up past glories in more than a few ways. But if that was the kind of performance you were looking for out of The Ravens after sitting through too many maudlin starched-shirt recitals, then even if it’s slightly derivative in structure and concept you’ll be giddy upon hearing this unfold.

A Place To Lay Your Head

With so much about it to celebrate it feels almost sacrilegious to chip away at those plaudits in the next breath, but as great as this sounds there’s always other aspects to consider beyond just the overall aural impression it leaves on your senses.

Though it wasn’t advertised as such, the similarities to two of their biggest hits, Write Me A Letter, and more pointedly its sequel, Send For Me If You Need Me, are unmistakable.

The basic plot and the phonetic similarities to those records will have you doing a double take at times and lead you to believe that I Don’t Have To Ride No More was in fact the third part of a trilogy. There are even moments when you may think the word that makes up the focal point of the title – “ride” – is actually “write” and by substituting that word it fits in even more with the evolving story of the earlier records.

If you remember in the first chapter of this saga he was asking his girl, whom he wasn’t seeing as much as he wanted, to write to him so he’d know she still cared. In the somewhat less imaginative follow-up he reports that she did in fact do so in the time since we last met them and now he was telling her he was ready for a bigger commitment and that should she request his presence he’d pack his bags and join her right away.

So if you WERE to assume that he was now singing “I don’t have to WRITE no more” it’d make perfect sense, especially because he then reports that she told him to basically live with her and ”put your shoes under mama’s bed”, implying a permanence that would be a fitting conclusion to the tale spread over three records.

I’ll even go so far as to suggest that’s what he originally wrote, whether actually put those lyrics on paper or just sang them off the top of his head, all in an effort to recapture that initial burst of creativity. But if he did so he may have soon realized that two and a half years was a long time to expect listeners to remember the first installments, or perhaps he didn’t want to merely repeat himself and so “ride” easily replaces “write” and with that it becomes an entirely different song and meaning.

But the problem is the meaning itself – which includes his girl hitting the numbers and collecting a substantial amount of bread thereby allowing him to live off of her winnings – are rather vague and a little unsettling. It also makes him saying I Don’t Have To Ride No More a little harder to figure out.

Does he mean he doesn’t have to ride to and from work? Or ride around the country like a traveling salesman, or for that matter like the star of a singing group who were always on the road?

We’re never really sure because the story here is secondary, giving a little more credence to the idea that it came about as a variation on an earlier song and was modified along the way to suit their musical needs more than their storytelling needs.

Just Hit The Numbers

But while all of that speculation into its creative concept is not completely irrelevant, it’s definitely secondary to the bigger story which is that the record itself sounds tremendous, a welcome return to what they do best.

This explodes with energy, taking full advantage of its faster pace to really ramp up the excitement so that you sort of overlook the confusion in the narrative. It also lets all of the Ravens share in the glories with their enthusiastic harmonies which at times have been in short supply as of late and to top it off Ricks’ performance gives just a hint of something naughty going on behind those doors he’s about to walk into so that it satisfies every need a fan of these guys has been asking for – but not always receiving – since they’d become among the first icons of the rock era.

Though it may be something of a closing chapter in that initial era’s story I Don’t Have To Ride No More essentially serves as the perfect way to mark the transition from the Forties into the Fifties as it cracked the national charts in February and was “riding” on territorial charts all winter, proving beyond a doubt that the sound they pioneered was here to stay.

You’d think this would be enough to keep them headed in the same direction but as always with these guys – or their record label – it’s never quite that easy. But as long we get enough of these types of songs to keep us happy then I suppose they can go back on the road peddling cheap plastic trinkets in between stops.

Since the numbers his girl picked that proved to be the winner were “six ninety-four” let’s use that as the basis for our score, splitting the difference between a six and a “94”, or a nine and a half (which we don’t hand out, but you get the idea). That would come to 7.7, probably the exact score I would give it if we used decimal points, but since we’re so glad to hear them sounding this boisterous again we’ll be more than happy to round it up.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of The Ravens for the complete archive of their records reviewed to date)