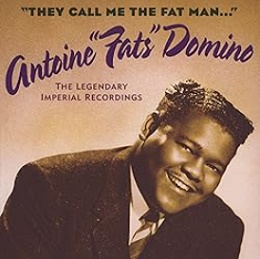

Fats Domino: “Don’t You Lie To Me”

23 Wednesday Feb 2022

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

Share it

IMPERIAL 5123; MAY 1951

The first few years of Fats Domino’s career have lots of great records with some impressive hits scattered among them but he hadn’t yet found the consistency he would become known for.

That was easy enough to understand, he was a novice songwriter at this point and Imperial was somewhat unsure about what was most marketable so they went down a few different paths before it became clearer what really worked best.

Ironically one of the records which pointed them in the right direction wasn’t an original song at all, but once it was interpreted by Domino’s distinctive vocals it becomes hard to ever think of it being done by anyone else.

Let’s Talk It Over Before We Start

Though the role that blues played in rock has for the most part been drastically overstated over the years there definitely were figures who seemed to be foreshadowing rock ‘n’ roll and whose style seemed much closer to it than the more traditional Delta blues approach.

Tampa Red has, for the most part, been mostly left out of the discussion, despite being far more closely connected than many more famous acts in the genre.

His career had spanned almost the entire era of modern recording, as way back in 1928 he and Georgia Tom (before he morphed into the creator of modern gospel, Thomas Dorsey) cut a truly immortal song, It’s Tight Like That and now in 1951 he released She’s Dynamite. These aren’t rock records by any definition of the term but they both have a structure that is easily adaptable… in fact B.B. King quickly covered the latter and it was as close to rock ‘n’ roll of this period as he got.

Don’t You Lie To Me was a song that Tampa Red wrote (under his real name, Hudson Whittaker) back in the early 1940’s and at first blush – taking into account the acoustic guitar and Red’s vocal tones – it doesn’t seem to have much in common with the proto-rock songs of this era like Rosetta Tharpe’s Shout, Sister Shout, or Champion Jack Dupree’s Big Time Mama or Lionel Hampton’s Flying Home, at least the section where Illinois Jacquet tears it up on sax.

Heck, Tampa Red’s own Let Me Play With Your Poodle came out at the same time and on the surface that notoriously racy song has more similarities to a rock aesthetic than this.

But when you strip away the sonic presentation of it – including the dreadful kazoo – the actual foundation of the song can be easily reconfigured for rock… as Fats Domino first showed.

Other than instrumentation and the vastly different textures of their voices Fats makes this sound as natural as a rock song as his own compositions, which is really saying something.

You Give Me All You Lovin’ If I’ll Give Mine Too

Before Domino even opens his mouth it’s his hands which get this transformation underway. His rolling boogie is incredibly infectious and a welcome sight as it’s something that hadn’t been featured on a single of his since last July. It’s got a slingshot effect here, hurtling the song out of the starting blocks and allowing what follows to ride comfortably in its wake.

Don’t You Lie To Me is not one of Domino’s better vocal performances from a technical standpoint. Until his tonsils came out in 1954 he had a higher pitched voice, which was fine, but here he’s got more of a nasal tone for some reason and that combination throws you off a little.

Yet he’s still got plenty of character in that voice which helps to offset the tonal qualities and here it’s a unique blend of feelings that shades his singing, his wounded pride coming through loud and clear even as he’s trying to lay down the law and make forceful demands of his girl.

That helps to soften some of the lyrical implications as the story unfolds. Though on the surface it’s a simple premise of right and wrong – lying is wrong, particularly as it pertains to infidelity – the message being delivered here is rooted in insecurity and we all know that insecure guys are prone to far worse offenses to try and resurrect their crumbling sense of manhood. Though the threat he makes is vague – ”it makes me mad and I get evil as a man can be” – it’s not without certain implications that are pretty clear.

How you handle that aspect of the composition is the telling part of any rendition as this is a guy who’s worried about losing his girl because of his own lack of self-worth, not because of anything she’s actually DONE yet, and so he’s proactively attempting to stave off the idea of her flirting or cheating with someone else by acting tougher than he is but also, as is evident in the rest of the lyrics, pledging his own devotion to her if she’s true to him.

It’s to Domino’s credit that he understood this internal struggle better than anyone else who sang it, Tampa Red included, but also Chuck Berry and The Rolling Stones, both of whom mimic Fats’s pacing but largely avoid providing any real emotional subtext in their deliveries. The Pretty Things by contrast lean into the menace more than the hurt which gives it a much more ominous feel… good in its own right even if it suggests more problematic behavior.

Fats on the other hand finds the perfect balance and with the faster tempo of his piano further cushioning it against the harsher aspects of the lyrics it goes down easier than if you were to take the song at face value for the troubling psychological implications it contains.

A Thieving Man

What’s not quite as palatable however is the backing track, something which was unexpected to say the least unless you know the story behind it.

The dominant musical feature of the song is the aforementioned piano, which is fantastic. Not only does it provide such an inviting introduction to the record but Fats returns for more of the same on the instrumental break and knocks it out of the park. You could strip everything else away, lyrics, singing and band, extend the piano workout and have a great record.

But where it misses the mark is in the horn section and it’s important to note that this came from the second session without Dave Bartholomew, after he and Lew Chudd, owner of Imperial, had a rift because Chudd had paid Al Young, the white owner of a local record store who had been trying to horn in on Domino from the start, a $1,500 bonus for “promotion” without giving anything to Bartholomew who co-wrote, produced, arranged and put together the band for the sessions.

An indignant Bartholomew rightly quit and Young, desperate to prove he was deserving of the credit he’d been claiming was rightly his all along, came in to produce.

The band is Domino’s road crew, all really good musicians but mostly unaccustomed to studio work. Unlike Bartholomew who pioneered the overlapping, interlocking arrangements for rock, the charts for Don’t You Lie To Me are simplistic and with just Wendell Duconge (alto) and Buddy Hagans (tenor) the horn section is underpowered. On top of that the circular refrain they play that serves as the underpinning to the song is out of tune with the vocals. Young was unable to hear this as he had no musical training and the record can’t help but suffer for his ineptitude.

Almost as bad is the fact that nobody is taking advantage of the musicians that are there, specifically Tenoo Coleman’s drumming, which isn’t given enough presence in the mix. The left-handed drummer was hellacious on the skins in live gigs with his thunderous fills yet the only opportunity he gets here isn’t even highlighted like it should be.

In the end this record wasn’t produced, it was simply recorded.

I’ll Be With You ‘Til The Cows Come Home

It’s a testament to any artist’s skill when their own talent can not only redeem a record that has some obvious flaws but actually make it well worth hearing. Although he was barely one year into his career, Domino’s skills are unquestioned and this record is further evidence of that.

He’s got a good song to work with for sure but what shines in this version of Don’t You Lie To Me are the aspects that are unique to Fats… the storming piano, the nuanced vocal inflections and intuitive understanding of the mindset behind it… which are more than enough to recommend the record in spite of the few drawbacks.

There’s also the fact that in the rock scene of 1951 Domino’s “sound” was unique enough to stand out and his voice, even if it seems like he was nursing a cold here, is already identifiable and a welcome presence in anybody’s playlist.

It’s far from his best work maybe but even a slightly compromised Fats is better than none at all.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of Fats Domino for the complete archive of his records reviewed to date)