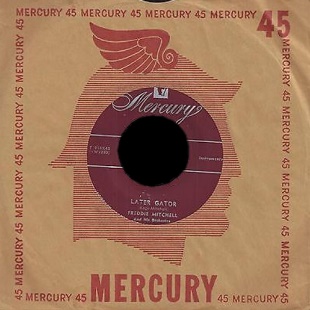

Freddie Mitchell: “Later Gator”

12 Monday Feb 2024

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

MERCURY 70018; DECEMBER 1952

This is hardly the most likely review to hand out important insight on life.

For one thing it’s not a big enough record by a big enough artist to be able to reliably count on casual readers dropping by to learn this vital lesson. Secondly, even the title doesn’t give you any indication that what you read here is going to impart any real insight.

But here goes…

When it comes to music, age is not an asset. Experience does not equate with quality. And major labels who think otherwise are always going to be at a huge disadvantage for not accepting this.

Left Word…

On one hand you have to at least admire the attempt that Mercury Records has made to come to grips with rock ‘n’ roll.

In fact they’ve done it twice, first with a rash of New Orleans acts in 1950 that resulted in one big hit and some uncharted gems to go along with it, leaving you to wonder why they didn’t follow that up with more sessions… or heck, even release all of the sides they already had in the vault from those acts.

More recently they’ve taken a slightly different approach by seeking out older rock artists with recent commercial success, perhaps believing that their age would make them amenable for whatever edicts from on high the label handed down should this rock ‘n’ roll “fad” fizzle out, as the company surely expected – and hoped – it would eventually.

But that hasn’t worked. Johnny Otis got his only hit for them when he illegally brought in relative youngster Mel Walker from another label and now an imminent court order will prevent them from releasing their records because of the contract violations.

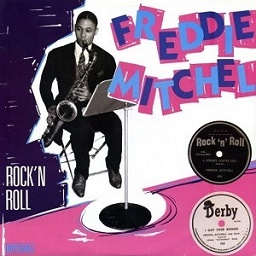

Their other big signing was sax star Freddie Mitchell, somebody who to them must’ve seemed like a safe bet. He’d scored some hits, had recorded dozens of reworked versions of ancient songs that were at least recognizable to the fogeys in the Mercury board room, and Mitchell had doubled as the head of Derby Records studio band, backing others on a few nice records along the way.

As if that wasn’t enough he was thirty-four years old now, a veteran of jazz bands in his younger days, and therefore while he might be a legitimate rock act, he was probably also capable of playing something more agreeable to the corporate mindset if it came down to that.

But what Later Gator was supposed to be is anybody’s guess.

Is this something designed to pull in the young rock fan, or a record to appease their parents, grandparents or crazed uncle locked in the sanitarium and let out for Thanksgiving dinner, provided he’s heavily sedated and supervised by armed guards?

I’m betting on the latter… and if that’s the case would someone mind if I used the sedatives myself before the song is cued up again? Thanks.

I Went Downtown

I like the percussion… let’s get that out of the way. It’s the best aspect of this track, especially the quirky jittery intro which is hypnotic, though far too short.

It keeps up appearances as more instruments join in, but tends to get drowned out by the… UGH… “singing”.

At least I think that’s the word for it. Luckily it doesn’t last long, it’s just a vocal intro to the meat of the song, but we’ve seen what happens far too often when these saxophonists take their lips off their reeds and let words spill out and it usually isn’t pretty.

This is when you wish Freddie Mitchell was born a mute.

Then again, when he stops his speak-sing prelude, he doesn’t immediately make up for it by blowing anything really appealing on his saxophone. Instead he let some trumpeter come along and take this too far away from the rock gutters that we wallow in and from this point forward we’re left scratching our heads if not beating them against a brick wall.

I’ll be reasonably fair-minded about this and say that Later Gator, in another context, might be… well, intriguing. Not necessarily good, but something that has the ability to keep your focus because you’d be wondering what kind of scene they were painting here with their Vegas glitz meets roadhouse arrangement.

The brass are of course the high-end of the class department straight from clubs with rigidly enforced dress codes. Mitchell’s sax, once it gets going, is more at home at the kind of club where dressing is optionally… especially after the clientele has been grinding away against one another’s bodies in a small overcrowded room with no air conditioning in the heat of summer down South.

The two sounds don’t exactly clash in the arrangement itself, as their parts are staggered enough to keep them at a distance, but they clash in your sensibilities and as a result neither one achieves the desired effect.

Maybe had this been in some B-movie film noir, but with that brass you’d need it in color which would more or less remove it from the genre, just as the brass threaten to remove the song itself from the rock genre.

When Mitchell voice starts squawking again as the song winds down asking if anyone’s seen Louise, I can tell you that she beat me out the door by a half a step and caught a speeding taxi by its bumper, pulling it to a stop just long enough to climb in and offer the entire contents of her pocketbook, the deed to her house and her firstborn child to the driver if he’d get her out of this part of town in a hurry.

All I know is I’d have offered more.

Later Fellas

Okay, it’s not THAT bad.

Oh, it’s bad for rock ‘n’ roll, don’t kid yourself, but as a crazed hybrid record it’s at least… well, an ambitiously dreadful concept.

But that’s the problem we started off talking about, wherein major labels don’t understand current music trends yet not wanting to miss out on its commercial potential find aging artists familiar with rock ‘n’ roll and tell them to put it in a framework they can appreciate.

The result is Later Gator, which one has to believe was Freddie Mitchell’s way of trying to get unsuspecting music fans to think this record was done by Willis “Gator Tail” Jackson instead of him.

Nice try, Freddie, but we’re not fooled.

In the 1960’s the saying among rock acts was once you turn thirty you’re dead, no longer interesting and don’t have anything to contribute anymore… which was true then and true now. Rock is a young person’s game and while every so often there’s an exception that proves the rule, the fact remains that the music changes too fast for those out of the current loop to keep up with.

Freddie Mitchell can still blow a sax something fierce, and there are passages here where he does just that, but at Derby he was hampered by the company insisting he revive standards because they were recognizable titles for an older audience. Here at Mercury he’s allowed to write his own songs, yet they either wanted him to bridge the eras, or he himself realized that when he was the age of the kids now dancing wildly to rock ‘n’ roll it was 1936 and he suddenly got nostalgic, which would explain the even more out of date throwback, Blue Coal, polluting the other side of this single

Or maybe he was on drugs.

Yeah, that’s a better story. He was definitely on drugs… at least that way he won’t be kicked out of the rock musician’s union and may even be feted at the next banquet for it.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of Freddie Mitchell for the complete archive of his records reviewed to date)